In recent years, while firmly establishing themselves in the domestic market, companies from certain Chinese industries have expanded into Europe and other developed countries, gradually stepping onto the center stage of the global arena.

Among them, the rise and internationalization of China's photovoltaic (PV) and new energy vehicle industries have been particularly dramatic. Their exchanges, mutual learning, competition, and cooperation with European counterparts have drawn significant attention and warrant thorough analysis.

Let's first look at the photovoltaic industry.

Photovoltaics is a technology that is both ancient and new. As early as 1839, French scientist Edmond Becquerel discovered that when light shone on two metal electrodes immersed in a conductive liquid, the electric current increased—a phenomenon known as the photovoltaic effect. Over the next century, countless scientists attempted to use this technology to convert solar energy into electricity.

In 1954, Bell Labs in the United States developed the first single-crystal silicon solar cell, making industrial-scale application of PV technology a possibility for the first time. The oil crises of the 1970s and the rising awareness of environmental protection spurred substantial U.S. investment in PV technology development.

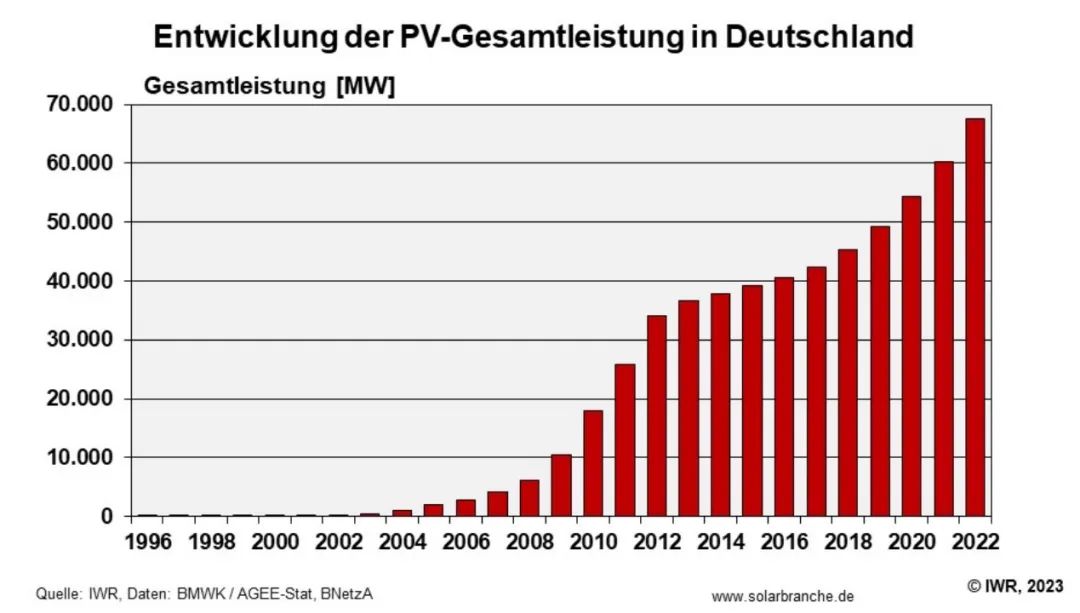

At the turn of the new millennium, Germany dominated the global PV sector. At that time, Germany’s Red-Green coalition government (comprising the Social Democratic Party and the Green Party) passed the Renewable Energy Act (the famous EEG), significantly increasing subsidies for the photovoltaic power generation industry. This made solar power a profitable and predictable business. German PV manufacturers gradually grew into leaders in the global market, and by 2011, employment in Germany's PV sector exceeded 150,000 people.

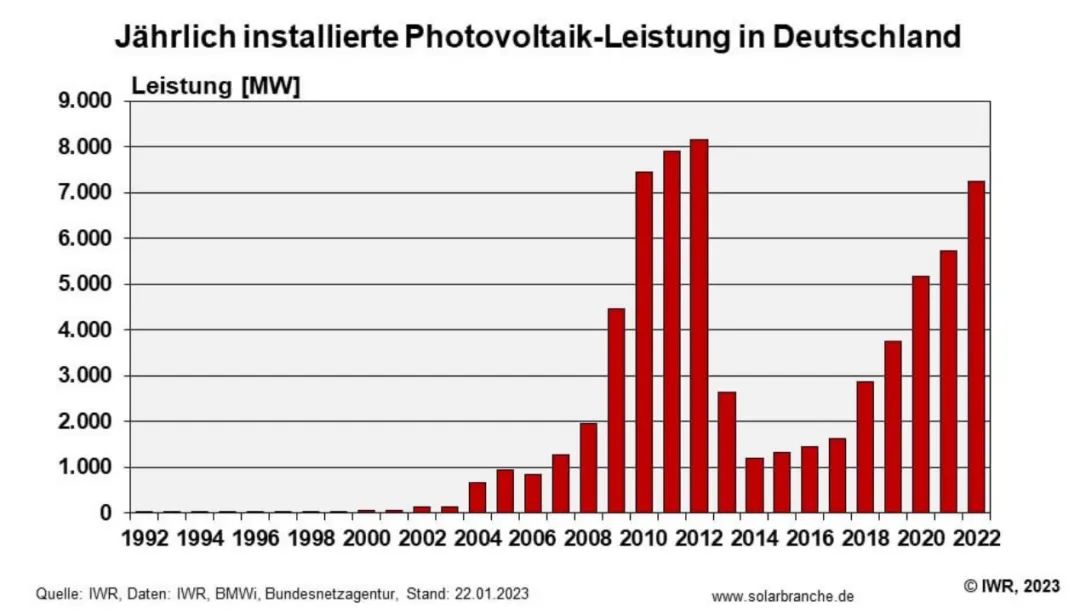

|Germany's annual photovoltaic installations over the past three decades. This chart more clearly shows that, as of 2022, installations had still not recovered to the peak levels of 7.5–8 GW seen between 2010 and 2012. Source: same as above.

At this time, across the continent, China's counterparts were also going through extremely difficult times. In 2012, Europe and the United States raised the "double anti" (anti-dumping and anti-subsidy) banner against China, imposing high "double anti" tariffs of 23% to 254% on Chinese PV exports starting from the end of that year. The following year, China's exports to Europe and the U.S. plunged by 50% and 70% respectively. The entire industry fell into widespread losses, and hundreds of companies went bankrupt.

In hindsight, the "double anti" policy was a "hurt the enemy by 800, but damage oneself by 1,000" move for Europe. Europe's domestic PV industry did not experience healthy growth as a result of the anti-China measures. Instead, due to reduced domestic subsidies and high costs, the market shrank. By 2016, Europe's total PV installed capacity had plummeted from 24 GW five years earlier to around 6 GW, hitting a historical low.

The darker the night, the closer the dawn. Ten years on, China's PV industry not only survived but experienced a rebirth.

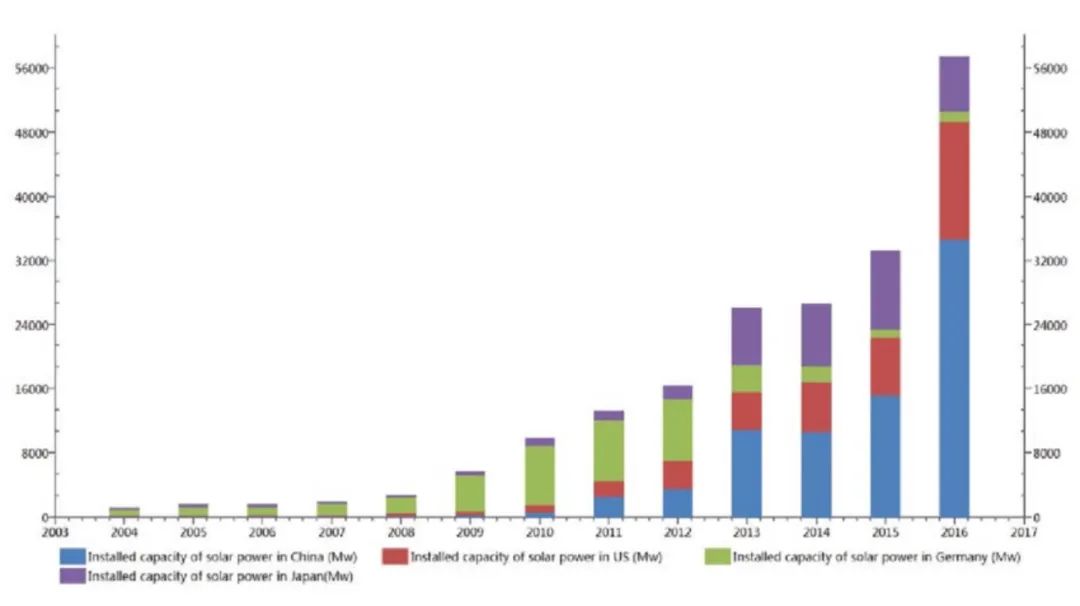

On one hand, the Chinese government intervened promptly, providing stable feed-in tariffs and strategically phasing down subsidies, which nurtured the domestic market. Quietly, China became the world's largest PV installer.

On the other hand, Chinese PV companies, once painfully over-reliant on "three external dependencies" (raw materials, equipment, and markets), deeply reflected on their vulnerabilities. They undertook comprehensive rethinking and action in technological development, global overall arrangement, and business models. A new generation of leading enterprises, represented by LONGi Green Energy, not only reached the global peak in production capacity but also emerged at the forefront of driving global technological evolution.

|In 2015, China surpassed Germany to become the country with the largest cumulative photovoltaic installed capacity in the world, and has since pulled far ahead globally. In the chart, blue represents China and green represents Germany.

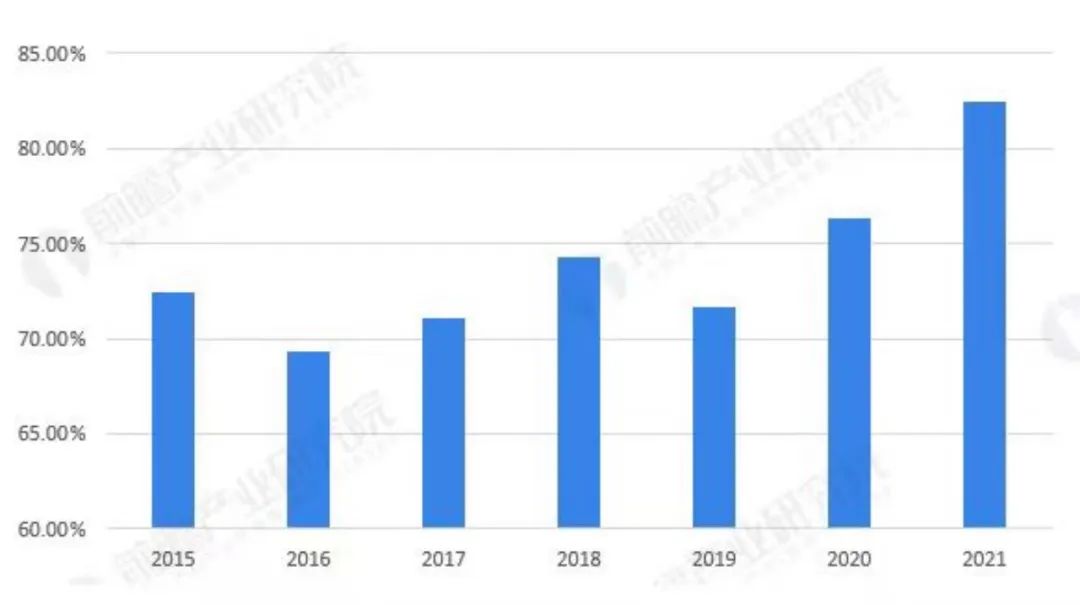

As of today, according to data from the International Energy Agency (IEA), 76% of all solar modules installed globally in 2021 came from China, with solar cells and silicon materials reaching 88.4% and 78.7%, respectively.

The top destination for China's exports is Europe, accounting for nearly 56%, followed by the Asia-Pacific region and the Americas.

Unlike before, China's domestic market has been the world's largest for eight consecutive years, enabling Chinese companies to enter a virtuous cycle of "market growth — technology upgrade — market growth." A relevant EU research report points out that Europe had a production capacity of 8 GW in 2021, whereas China developed approximately 300 GW of capacity over the past 15 years, highlighting a significant disparity.

|Proportion of China's photovoltaic module production in global output from 2015 to 2021. Source: China Photovoltaic Industry Association, Qianzhan Institute.

According to calculations by Germany's Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, photovoltaic capacity must increase from 60 GW to over 200 GW by 2030 for Germany's energy transition to succeed. To meet this goal, Germany would need to install more than 17 GW annually over the next eight years, compared to only 5.46 GW in 2021 and 7.18 GW in 2022.

In terms of products, currently only about half of the solar panels sold in Germany are manufactured domestically. For example, in 2021, domestic production reached 2.8 GW, while the other half was primarily imported from China. In 2022, 87% of the solar PV components imported by the EU came from China. Jochen Rentsch, an expert at the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems, pointed out, "If you're looking in Europe for equipment to produce solar wafers right now, you simply won't find a non-Chinese manufacturer that's competitive. Put simply, we need machines from China to free ourselves from dependence on China!"

In recent years, concerns have emerged among European governments and businesses about how geopolitical conflicts or potential Chinese export restrictions could impact industry development. Recently, 24 German companies sent an open letter to the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs, proposing policy recommendations to revitalize Europe's photovoltaic industry and reduce reliance on China.

The letter notes that Germany's current production capacity accounts for only about 1% of the global total and calls on policymakers to take action to expand Germany's manufacturing capabilities in solar technology. An increasing number of German media outlets are focusing on how Germany and the EU can regain leadership in the PV industry, frequently analyzing policy measures, industrial training, industry-academia-research collaboration, and investment facilitation from multiple angles.

While certain political and media figures in Germany and Europe continue to emphasize the risks of "over-reliance" on China, such dependence is actually mutual. Chinese PV products are similarly dependent on the European market, which currently accounts for nearly half of China's annual PV export value.

In recent years, new photovoltaic policies have been introduced in Europe, the United States, and even India to support domestic manufacturing and encourage the establishment of local supply chains. Combined with various trade investigations and barriers, these measures pose significant risks and challenges to China's PV industry.

In March this year, the EU released draft versions of the Net-Zero Industry Act and the Critical Raw Materials Act, both aimed at promoting the return of manufacturing—including the PV industry—to Europe, while advancing the continent's green transition.

The competitive and cooperative relationship between China and Europe in the photovoltaic sector is entering a new chapter.

The gap between China's automotive industry and the world's leading level was once considered an insurmountable chasm.

In the early days of reform and opening-up, German automakers visiting China to assess the investment environment were deeply shocked by the primitive state of China's automotive sector.

In 1978, a German journalist accompanying Volkswagen's delegation to China remarked, "Volkswagen is about to produce cars on an isolated island with no parts suppliers whatsoever," and commented that "the hoists, long benches, and rubber hammers in Chinese workshops are production methods from my grandfather's era."

At that time, among more than 2,500 auto parts manufacturers across the country, nearly all were operating at a level akin to a small-scale peasant economy. From the first assembly of a Shanghai Santana sedan on April 11, 1983, to 1985, the localization rate of the Santana over three years was merely 2.7%. Chinese suppliers could only produce four components: tires, horns, antennas, and nameplates. For critical parts essential to car manufacturing—such as engines, chassis, bodies, and frames—Chinese companies were unable to produce a single one.

|In 1978, an approval document from the First Ministry of Machine Industry and the Shanghai Revolutionary Committee regarding the introduction of foreign automotive technology in Shanghai. After repeated negotiations with several international automakers, Volkswagen emerged as the first choice, eventually leading to the establishment of a joint venture between the two parties.

Until the early 21st century, although China's automotive industry had made tremendous progress, the gap with its Western counterparts remained significant. Take crash tests—mandatory for selling cars in Europe—as an example: Chinese automakers' test results were shockingly poor, with some car models even receiving one-star ratings, a rare and dismal outcome.

As a result, Chinese-made vehicles struggled to enter markets in Europe and North America, often being limited to sales in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. They were generally priced low and suffered from weak brand recognition.

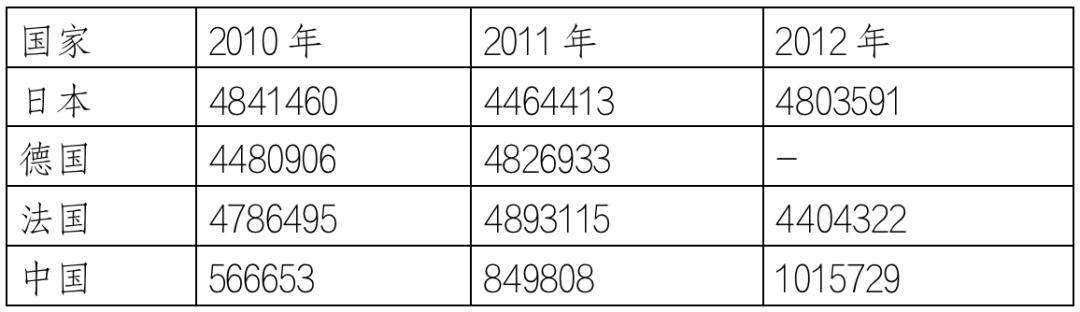

It was not until 2012 that China's auto exports barely reached the milestone of one million units. At that time, Japan, Germany, and France each exported four to five times more vehicles annually than China.

|Automobile export volume statistics for major countries from 2010 to 2012. China barely made it into the top ten, while Japan, Germany, and France firmly occupied the global top three. Source: China Automotive Industry Yearbook.

Times change like the tide, and quietly, undercurrents began to stir in the global automotive industry, with major trends such as electrification, intelligence, and connectivity gradually becoming the mainstream direction. While countries around the world were still hesitating and observing, the Chinese government decisively chose to act.

Between 2009 and 2010, the government began offering subsidies to individuals purchasing new energy vehicles (NEVs), including electric cars, and provided various preferential policies—including direct subsidies—to related manufacturers. At that time, annual nationwide sales of NEVs amounted to only one or two hundred thousand units.

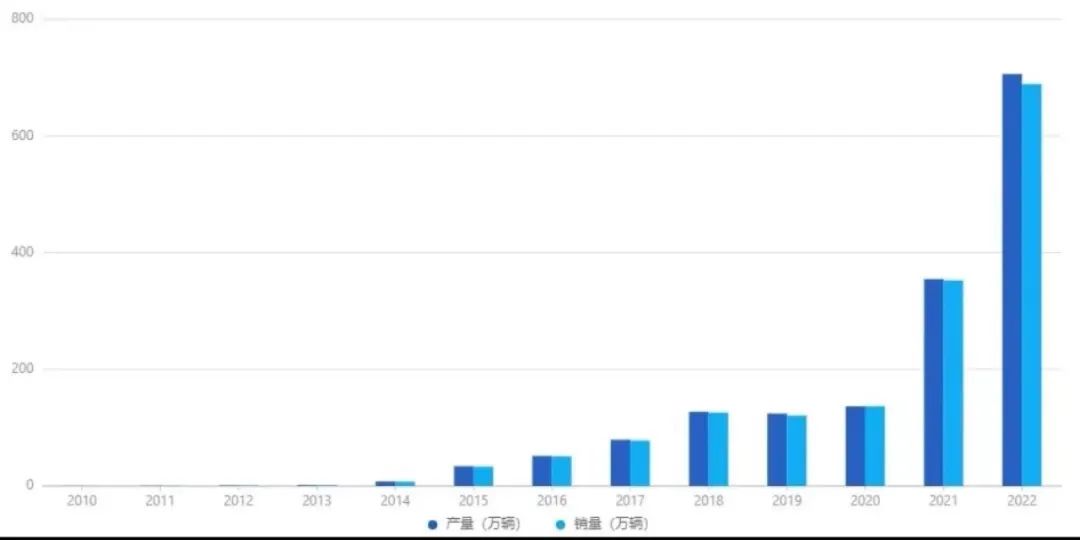

Over the course of more than a decade, China introduced more guidance documents and policy regulations for new energy vehicles than any other country. For example, in 2014, government departments under the State Council issued over 30 new related policies. This period saw the emergence of new automotive startups—NIO, XPeng, and Li Auto. In 2015, China's NEV sales reached 331,000 units, securing the top spot globally.

|China's annual production and sales of new energy vehicles from 2010 to 2022, surging from just a few ten thousand units to nearly seven million, an increase of hundreds of times. Source: Starlink Energy.

Looking back at the history of China's automobile exports, the figure was only 20,000 units in 2002 and first surpassed 1 million in 2012. For nearly a decade afterward, exports remained stagnant, even dropping to 600,000 units in some years, trapped in a bottleneck. It was not until 2021, with the rise of new energy vehicles—especially electric vehicles—that this stalemate was truly broken.

In 2022, China exported a total of 3.111 million vehicles, a substantial year-on-year increase of 54%, surpassing Germany to become the world's second-largest auto exporting nation. Among these, new energy vehicle (NEV) exports reached 679,000 units, soaring by 120%.

In the first quarter of this year, China exported 1.07 million vehicles, compared to Japan's 954,000, positioning China to potentially become the world's top auto exporter for the first time.

Climbing higher on the crest of the wave and rowing forward, boundless vistas lie ahead. According to data from the International Energy Agency, about 35% of global electric vehicle exports in 2022 originated from China, making us the global leader in sales of new energy vehicles, especially electric vehicles, power batteries, and other key components.

A recent report by market research firm EV-Volumes indicates that last year, approximately 10.5 million new energy vehicles were sold globally, a 55% increase from 2021. Chinese automakers, including Tesla's Shanghai plant, sold nearly 6.9 million units—a year-on-year surge of 82%, far exceeding the global average. In comparison, North America saw growth of 48%, while Europe grew by only 15%.

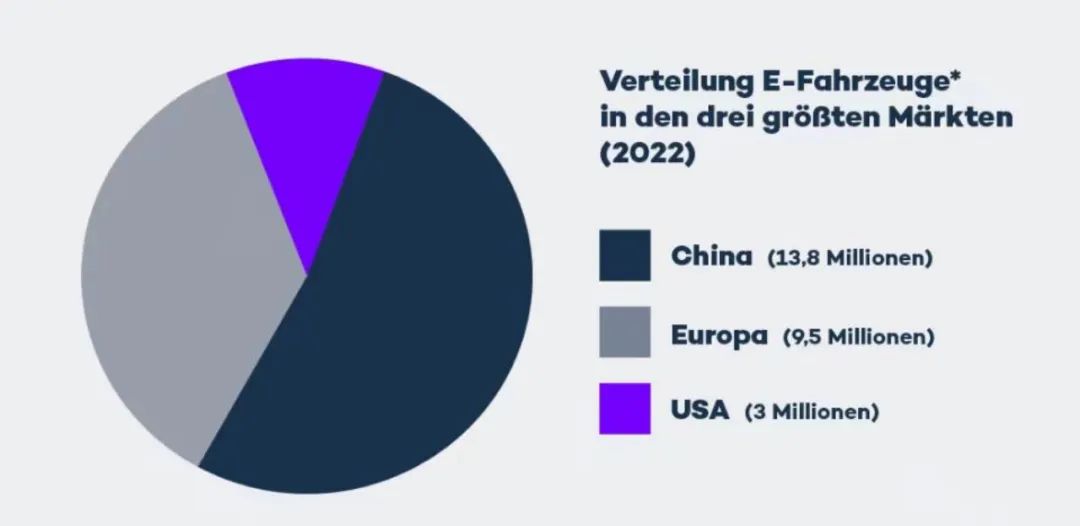

|In terms of global market share for electric vehicles, China has surpassed the combined share of Europe and the United States. Source: IEA Global Electric Vehicle Outlook 2023.

At present, Europe has become the largest trading partner of China's electric vehicles and batteries. In 2022, the share of electric vehicles sold by China to the European market will increase rapidly to 16%.At the same time, the average export price of China's automobiles is also increasing, and even the price in the European market is generally higher than that in China. The data shows that the average export price of automobiles in China was $12,900 in 2018, and increased to $18,900 in 2022, which increased by about 50% in four years, and the price of some models was 40% higher than that in China.As a core component of electric vehicles, China has been in a leading position in the field of power batteries in terms of supporting the industrial chain. In the first half of 2022, six of the top ten global installed capacity came from China.In addition, in recent years, China has accumulated profound technology and commercial applications in many fields, such as 5G, AI, cloud computing and big data, which coincides with the great changes in the automobile industry towards human-computer interaction and intelligent networking. Therefore, China electric vehicle enterprises naturally participated in and even led this intelligent change.In the domestic market, the share of China brand has exceeded 50%, while the market share of foreign brands such as Europe has declined. In 2022, BYD surpassed Volkswagen's joint venture company FAW-Volkswagen to become the domestic sales champion.However, Europe, as the third largest automobile market and the second largest electric vehicle market in the world, is making great efforts to catch up in recent years. On the one hand, European countries' subsidies and support for electric vehicles are constantly improving, and the market acceptance is increasing; On the other hand, the sales of electric vehicles in Europe have increased sharply, reaching 1.577 million units in 2022, which is almost the same as the sales of fuel vehicles of 1.637 million units, and the market penetration rate is twice that of China.In recent years, dozens of domestic OEMs and spare parts manufacturers have settled in Europe, carrying out sales, setting up R&D and even preparing to invest and set up factories. Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited's first overseas factory in Thuringia achieved mass production of lithium-ion battery cells as scheduled. The factory plans to invest a total of 1.8 billion euros, with a planned production capacity of 14GWh, which will provide a total of 2,000 local jobs.

Looking at China's photovoltaic (PV) and new energy vehicle (NEV) industries together, the deep-seated reason for their leapfrog development lies in their ability to simultaneously grasp international trends—learning advanced technologies and experiences from the West—while leveraging China's vast domestic market to scale up, strengthen, and innovate under timely and effective industrial policies. Similar patterns have emerged in recent years across multiple sectors, including home appliances, telecommunications, optoelectronics, and construction machinery.

Today, global competition in both industries is intensifying, with companies vying not only on technology and market share, but also on cost and efficiency. In the photovoltaic sector, in the early 2000s, the cost of one kilowatt-hour of solar power in Europe ranged from 50 euro cents to 1 euro. Today, it has dropped to just 2–6 euro cents. China, leveraging its dual advantages of scale and technology, has consistently maintained a price advantage of nearly 50% over European producers, keeping its products in strong global demand.

Previous European "anti-dumping and countervailing" (AD/CVD) measures against Chinese exports failed to achieve their intended outcomes—particularly in expanding and strengthening Europe's local PV industrial chain. As a result, Europe was forced to lift its punitive tariffs on Chinese PV products in 2018–2019. The core reason was China's overwhelming, decade-long buildup of a low-cost, high-efficiency industrial advantage.

The NEV industry follows a similar pattern. High market prices, limited model choices, and slow business decision-making have significantly delayed the timely transition and market capture by European automakers—particularly German brands—into the new energy vehicle sector.

As China's domestic market continues to grow at a leapfrogging pace, an increasing number of German component suppliers are being drawn to China to support Chinese automakers. For example, Bosch announced early this year a new R&D and production center in Suzhou with an investment of 950 million euros. ZF Friedrichshafen’s CEO, Wolfgang Sander, stated that the company has learned a great deal from China's speed, and that long-term competitiveness would be lost if they were to leave.

A recent report by Allianz, titled "China's Challenge to the European Automotive Industry," highlights that European automakers now face a dual challenge:

Domestic Chinese EV manufacturers are expanding their market share in China, potentially leading to declining sales for European automakers in the Chinese market.

Chinese-manufactured electric vehicles are seeing rising sales in Europe.

In the future, without commercial success in and with China, European and American automakers may struggle to maintain or achieve global leadership.

Volkswagen's software subsidiary CARIAD has already established joint ventures with Horizon Robotics and Thundersoft. BMW Group has announced it will begin producing the groundbreaking all-electric BMW Neue Klasse models in Shenyang starting in 2026. These are the latest examples of European automakers striving to catch up with this wave of innovation in China.

Today, China possesses both a massive, high-quality labor force and a huge, rapidly growing market—rare in Western countries—while also offering the engineering talent, innovation, and R&D capabilities uncommon in other developing nations. Furthermore, investing in China comes with a series of unique global advantages, including excellent infrastructure, low energy prices, a leading 5G network, and a stable policy environment.

China's advantages over developed Western nations or other large developing countries are no longer confined to a single or a few sectors. In terms of comprehensive comparative advantages, China is a truly "unique" nation on the global stage. European companies that deeply integrate into China's industrial chain often achieve lower costs and enjoy investment returns significantly higher than those in other regions over the long term, making the Chinese market difficult to relinquish.

At a deeper level, energy, transportation, and communications have always been the pillars of industrial revolutions. The NEV and PV industries involve far more than just national green transitions and carbon neutrality strategies—they are fundamentally tied to each country's future energy security.

As previously mentioned, the EU's promoted Net-Zero Industry Act aims to create a so-called "secure" business environment for European net-zero projects, boost domestic industrial competitiveness, create more green jobs, and ultimately achieve European energy independence—with a target of 40% self-sufficiency in net-zero products by 2030.

In reality, China has increasingly demonstrated comprehensive advantages in cost, efficiency, and supply chains in both sectors. Deliberately reducing or halting cooperation with China could damage the global competitiveness of European companies and make Europe's own carbon neutrality goals distant and difficult to achieve.

|能源革命往往是工业革命的先声

On the other hand, for Chinese enterprises, the prevailing geopolitical tensions and protectionism present new challenges to their global strategies. For example, against the backdrop of Western countries—particularly Europe and the United States—introducing new policies to subsidize domestic production in the photovoltaic sector, how to adapt to the changing landscape, prudently and proactively consider investing in local manufacturing after thoroughly analyzing regional policy dynamics, leverage this new energy revolution to secure greater influence in the global division of labor, integrate into local environments, and build mutually beneficial ecosystems—will be a central challenge for Chinese companies.

The difficulty of successful cross-border investment lies precisely in the inability to simply recreate the favorable conditions that led to success at home. In the electric vehicle sector, China currently leads the world in battery installations and charging infrastructure, with comprehensive supporting industries in critical areas such as raw materials, LiDAR, intelligent cockpits, motors, and electronic control systems. This has fostered a relatively complete and internationally competitive industrial ecosystem.

From the perspective of international operations, Chinese manufacturers have made a solid start in "going global." The key now is how to further "go deep" and "move up"—by establishing robust installation, service, and after-sales systems in host countries to achieve stable local production and sales capabilities; by leveraging local financing systems and supplier networks to fully utilize their own strengths; and by refining global strategies, talent deployment, and supply chain layouts. Continuously cultivating international brands, integrating into local societies, and gradually implementing R&D and marketing strategies tailored to local needs will determine the depth and quality of integration between Chinese enterprises and the industries and markets of their host countries.

Replicating one's own success is often the shortcut to achieving it abroad. When the day comes that Chinese companies can seamlessly integrate host-country laws, regulations, and business environments, develop unique yet market-relevant local products and business models, and learn to harness resources across government, industry, academia, and research to build entirely new ecosystems, perhaps an even vaster ocean of stars and seas will lie ahead.

本文装载自:秦朔朋友圈 ID:qspyq2015